“Where the real world changes into simple images, the simple images become real beings and effective motivations of hypnotic behavior.”

Guy Debord, Society Of The Spectacle

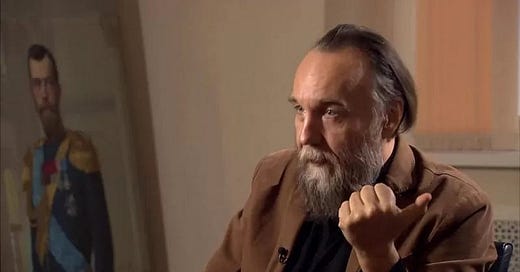

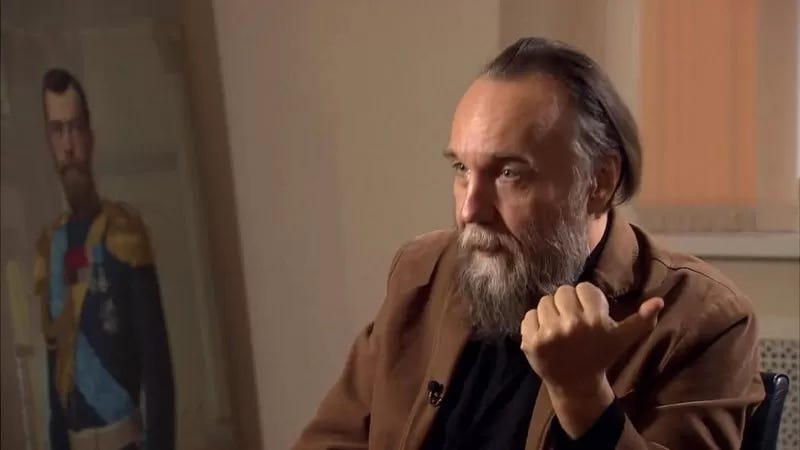

Alexander Dugin is a specter haunting the edges of Western politics—an ideologue and fabulist without official power who casts a long shadow over the global contest of ideas. He is no mere court philosopher whispering into Putin’s ear; he is something far more dangerous: a subversive architect, weaving ideological snares designed to trap the disillusioned.

In Russia, Dugin is a marginal figure, lacking the popular appeal of more charismatic ultranationalists like Egor Prosvirnin. His visions are also often too radical, too esoteric for the Kremlin’s pragmatic power brokers. Yet it is outside Russia—where uncertainty breeds desperation—that Dugin finds his most receptive audience. Fluent in English and supported by a network that swiftly translates his works into Arabic, Chinese, French, Spanish, and Persian, he has become a global propagandist, slipping his ideas into the cracks of Western discontent.

Dugin’s appeal lies in his ability to speak to the dispossessed of globalization, the disenchanted of liberalism and modernity. To those who feel cast aside by the forces of progress, he offers an intoxicating mythos: a world of civilizational struggle, where the West is not triumphant a crumbling empire destined for collapse. His words do not command armies, but they infiltrate minds—spreading through the fissures of Western polarization like slow poison.

At the core of his doctrine, laid bare in Foundations of Geopolitics, is a singular animosity toward the Anglo-American world. His cherished concept of “multipolarity” is not a vision of coexistence, but a call for confrontation—a euphemism for the destruction of the world order led by the United States and its Atlanticist allies.

For Dugin, Eurasian “land power” must rise to crush the Anglo-American “sea power,” and the Western-led order must be torn down, not reformed. By disguising his agenda in the rhetoric of sovereignty, pluralism, and decolonization, he has embedded his anti-Western narrative into global discourse, transforming “multipolarity” into an alluring rallying cry.

Dugin’s method is deceptively simple:

First, delegitimize the West—depict it as decadent, corrupt, and more importantly, inevitably doomed to decay. He thrives on feeding narratives of self-loathing, turning every crisis into proof of inevitable decline. As Europe reels from the aftershocks of Russia’s war on Ukraine—skyrocketing energy prices, economic strain, and political discord—Dugin reframes these hardships not as the outcomes of the Russian aggression, but as symptoms of a crumbling Western order. Meanwhile, he casts the United States—overstretched by global crises and paralyzed by domestic fatigue—as an empire in retreat, peddling isolationist rhetoric to weaken its resolve and hasten its withdrawal from global leadership.

Second, lull Western audiences into complacency by downplaying threats from powers like Russia, China, and Iran, framing them as misunderstood or defensive rather than expansionist. Central to this deception is the Russo-Islamic Pact, where he envisions a strategic alliance between Russia and key Islamic states, particularly Iran, to counter Western dominance. In reality, it is a tactical convergence where Moscow exploits Islamic grievances to weaken Western influence, advancing Dugin’s ultimate fantasy: an isolated and discredited West.

Third, weaponize the language of resistance—terms like “decolonization,” “Eurasianism,” and “multipolarity”—to dress Russian ambitions in the robes of liberation. Dugin’s ideological project does not end with the West—it extends to Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where he repackages Russia’s ambitions in the language of decolonization and anti-imperialism. To African nations, he offers Russia as a partner in resisting Western exploitation, concealing Moscow’s own extractive designs.

Fourth, infiltrate cultural and academic spaces to normalize his ideas under the guise of intellectual discourse. Through conferences, think tanks, and academic platforms, he carefully crafts the image of a philosopher rather than a propagandist, masking his subversive agenda in scholarly debate. By pursuing academic legitimacy, he reframes his ideology as serious political theory, making it more palatable to elites.

Fifth, exploit digital platforms to amplify division. By infiltrating online communities—both far-right and far-left—Dugin’s narratives reach disaffected individuals, fueling culture wars, conspiracy theories, and extremism that fracture social cohesion within Western democracies.

Sixth, co-opt religious and traditionalist movements to frame Russia as the guardian of civilization against a morally bankrupt West. By invoking “spiritual warfare” and aligning with conservative values on family, gender, and identity, Dugin forges an ideological bridge between Russian expansionism and Western culture warriors, positioning Moscow as an ally.

But his methods rely also on geographical and cultural disparities.

In Europe, Dugin’s anti-Americanism resonates with both far-right nationalists and far-left anti-globalists—opposite poles united by a shared contempt for U.S. hegemony and the perceived cultural homogenization of neoliberalism. His calls for a multipolar world strike a chord with those yearning for a Europe unshackled from Washington’s influence.

In America, his reach is more insidious. On the populist right, his traditionalism and nationalism appeal to those who believe the nation has been eroded by multiculturalism and moral decay. On the anti-establishment left, his rhetoric of decolonization and anti-imperialism masquerades as a radical critique of Western hegemony. In both camps, he exploits legitimate grievances not to inspire solutions, but to breed division.

Dugin’s influence lies not in what he builds, but in what he destroys. His mission is singular: to unmake the West, to turn its existential crises into collapse.

Debates in the West over whether Dugin is a fascist, a Nazi, or a serious Eurasianist are ultimately distractions. What truly matters is his subversive anti-Western agenda—one designed to undermine the United States, sow division, and weaken the West’s influence. Dugin thrives on ambiguity, using ideology as a weapon rather than a doctrine. Arguing over labels only serves his purpose, as it shifts focus from his actions to his persona.

Recognizing his agenda for what it is—a deliberate campaign of ideological warfare—is the crucial first step to countering his influence and neutralizing the chaos he seeks to unleash.

Honestly, I wonder if you're overestimating him. With so much ambient noise, who can hear such a singular voice? Plus, there are numerous forces larger than one grumpy ideologue in play. As you say, "Dugin’s appeal lies in his ability to speak to the dispossessed of globalization, the disenchanted of liberalism and modernity." These would be there anyway, without Dugin, no? Even if he's being funded by USAID -And who isn't?- Is his influence really any worse than, say, Andrew Tate's? Who is his audience?

Good analysis, I definitely see echoes of Dugin's opinions in some popular figures with bad takes but large followings, such as Candace Owens, Jackson Hinkle and other significantly dumber Twitter figures whose names I can't remember( but who are also quite popular). While elites choose from a more limited pool of worldviews that are relatively, if not perfectly consistent, a great chunk of people in Western societies today harbors feelings that are not fully right or left-leaning, but rather incongruously combine elements of both ideologies and simply stem from a sense of opposition to the Western-NATO order and the alienation of modern society. The idea of Russia, Iran and others as benevolent actors is too dumb for most intelligent people, although I recognize the U.S. order is also opportunistic, if perhaps slightly more evolved.