To my dad, who first told me this story when I was a teenager—and who always taught me to be the monkey brave enough to climb the ladder.

______

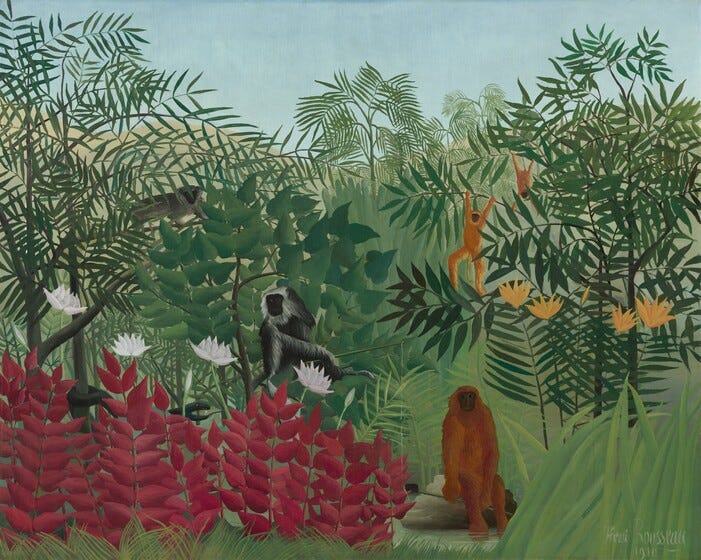

The Monkey Ladder Experiment is often invoked as a lesson in conformity and institutional inertia. Though the experiment itself never took place, its message endures—habits outlive their purpose, and traditions persist long after their logic has been forgotten.

In a 2011 Psychology Today post, Michael Michalko described it like this:

Psychologists placed five monkeys in a cage with a ladder and a banana hanging above it. When a monkey tried to climb the ladder, the others were doused with ice-cold water. The lesson was swift: climbing meant punishment for all. So they turned on each other, attacking any monkey that dared.

Then, the conditions changed. The cold water was shut off.

One by one, the monkeys were replaced. Each newcomer, seeing the banana, made for the ladder—only to be beaten down. Over time, none of the original monkeys remained. Not one had ever been sprayed with cold water, yet not one dared climb the ladder.

Why? No one knew. It was simply how things were done.

Though fictional, the story endures because it speaks to something true. Institutions—governments, bureaucracies, entire nations—cling to rules long after their reason for existing has faded. Policies built for a world that no longer exists remain in place, enforced by habit, upheld with suspicion, and defended against those who dare to question them.

Spinoza said, "Men believe themselves free because they are aware of their actions, yet they ignore the forces that shape them." Nations, like the monkeys watching the ladder, follow patterns they mistake for necessity. They repeat decisions inherited from a past they no longer understand.

Foreign policy is filled with ladders no one dares climb. Once a doctrine is established, it lingers—even when the world it was built for has long since vanished.

The world is never still. It shifts in ways both imperceptible and violent—sometimes unfolding over generations, sometimes unraveling overnight. Yet, within this movement, leaders cling to old assumptions, mistaking tradition for strategy and permanence for wisdom. They fight wars that no longer need to be fought, defend borders that no longer matter, and uphold rules that serve no purpose. They believe they are shaping history when, in truth, they are merely repeating it.

Power does not belong to those who cling to the past. It belongs to those who master change.

Henry Kissinger understood this. His genius was not in loyalty to any ideology but in his ability to see power for what it was—fluid, shifting, never bound to fixed principles. He knew that alliances were not sacred but strategic, that enmities were temporary, and that yesterday’s certainty could be tomorrow’s trap. His diplomacy was neither sentimental nor nostalgic—it was adaptable, precise, and brutally pragmatic.

The Monkey Ladder Experiment is more than a parable; it is a warning. A nation that enforces the past without questioning it is doomed to repeat it.

This was the logic of American foreign policy in the early Cold War. The Soviet Union was treated as an existential threat, an enemy to be countered at every turn, a force that had to be contained, confronted, and dismantled. Every war—whether in Asia, Africa, or Latin America—was framed through this lens. To lose anywhere was to lose everywhere.

Kissinger saw what others did not. He understood that the Soviet Union was not an unstoppable force, but a state burdened by contradictions—military overextension, economic inefficiency, political stagnation. He saw that the Cold War was not a two-sided battle but a multi-dimensional struggle, and that the most powerful move was not to fight the Soviet Union directly, but to divide its alliances, shift its focus, and force it onto the defensive.

So he did something no one else dared to imagine.

He climbed the ladder.

Instead of treating the Cold War as an ideological struggle, he saw an opening that no one else had: China. At the time, Beijing was dismissed as an implacable enemy, as irredeemable as the Soviet Union itself. But Kissinger saw deeper—he knew that China and the Soviet Union were not true allies, but rivals, locked in a quiet struggle for dominance within the communist world.

His secret trip to China in July 1971 was a masterstroke of realignment. With a single move, he fractured the communist bloc, forced the Soviet Union into a two-front geopolitical game, and reconfigured the global balance of power. What had once seemed like an unbreakable ideological alliance—Moscow and Beijing united against the West—was now splintered.

It was not just a diplomatic coup. It was a rewriting of the world order.

By forcing the Soviet Union to compete with both the United States and China, Kissinger accelerated its decline. The Cold War was no longer a contest between two superpowers but a triangle of shifting interests. The Soviets, once an unchallenged hegemon in their sphere, were now forced to divert their attention, resources, and strategy toward containing their own supposed ally.

The rules of the game had changed. And Kissinger had changed them.

The same principle guided his approach to the Middle East. His strategy was never about temporary crisis management; it was about constructing a new strategic order—one that would end the Egyptian-Israeli conflict and bring Egypt into the American orbit during the Cold War. He achieved this without ever compromising a single commitment to Israel.

His diplomacy was not about preventing war—it was about redrawing alliances, ensuring that the seismic shifts of the region would ultimately favor American interests. He understood that real power was not just about military dominance, but about building durable relationships, repositioning adversaries, and using war itself to create a more favorable peace.

Power is not something to be seized, nor a monument to be defended. It is a current—a force that moves through time, dissolving the structures men believe to be eternal. To master it is not to impose one’s will upon history, but to anticipate its motion, to sense its turning before others, to move with it rather than be buried beneath its weight.

The greatest folly of those who govern without vision is the belief that yesterday’s stability ensures today’s permanence. They mistake habit for wisdom, clinging to what was rather than seeing what is becoming. But as Spinoza observed, "Things are not more or less perfect because they have lasted longer, but because they agree more or less with their own nature." The world does not change by sentiment, but by necessity. Power does not announce its shifting—it moves in silent undercurrents, sensed only by those who do not mistake memory for foresight.

Enduring statesmanship is not the defense of a fading order—it is the ability to recognize change before it solidifies. History is not a cycle to be repeated, but a force to be shaped. Those who understand this command the future. Those who do not are consumed by it.

Superb observation but at the moment no one at the world stage has fully understand the change happening and going to happen in next decade...hence it's chaotic world right now

Beautifully written!

In broader terms, this is an allegory for dogma vs empirical discovery. We need dogma to establish beneficial norms and behaviors, without the need for everyone to constantly be searching for and making the same empirical discoveries. It is also true that the human spirit tends to instinctively revolt against all dogma at some point.

What is troubling right now is that we have this instinctive revolt against well-founded secular dogmas, such as "Vaccines are good", "Nazis were bad, Hitler was Satan", "Global warming is real"... I get the natural human drive to reject dogma, but these rejections are empirically wrong. I don't have a solution, just an observation and concern.