It is not the clear-sighted who rule the world. Great achievements are accomplished in a blessed, warm fog.

Joseph Conrad

While Western democracies were perfecting the art of precision—surgical strikes, counterinsurgency playbooks, data-driven campaigns—another actor was in the background, reverse-engineering the whole structure like a saboteur studying a skyscraper’s blueprints, looking not to scale it, but to bring it down from within. The prevailing belief was that overwhelming firepower equaled security. The truth? The foundations were already groaning. Loud wins on the battlefield masked quiet collapses in the architecture.

Western defense culture still thinks in flashes and bangs—mobilizations, incursions, missiles on the radar. It mistakes silence for peace, overlooking that subversion doesn’t march in—it seeps. Not with flags and formations, but through narratives, networks, and proxy fronts. A protest with no author. A bank transfer with no trail. An idea so native it evades suspicion—because it never had to knock on the door.

When these operations finally register on the radar, they’re labeled “interference”—a word that suggests clumsiness, not intent. As if democracy were a sound system someone leaned on by mistake. But this isn’t background noise. It’s doctrine. And it’s devastatingly efficient.

In 2013, Russian General Valery Gerasimov put this shift into writing. “The very ‘rules of war’ have changed,” he said—framing a strategic evolution where nonmilitary means weren’t just support acts, but in some cases outperformed firepower altogether. This wasn’t a fringe theory. It was a field manual for 21st-century conflict.

At the heart of this doctrine is inversion. In Gerasimov’s logic, the information space isn’t the prelude—it’s the battlefield. The public isn’t collateral—it’s the terrain. And military force? That’s the backup plan.

This isn’t a technological breakthrough—it’s a strategic one. While the West draws neat lines—red, legal, moral—this model thrives in the blur. It doesn’t contest deterrence. It walks around it.

Ambiguity is not a side effect, it’s the operating system. You don’t need to outrun a superpower—you just need to keep it second-guessing long enough to slow its stride.

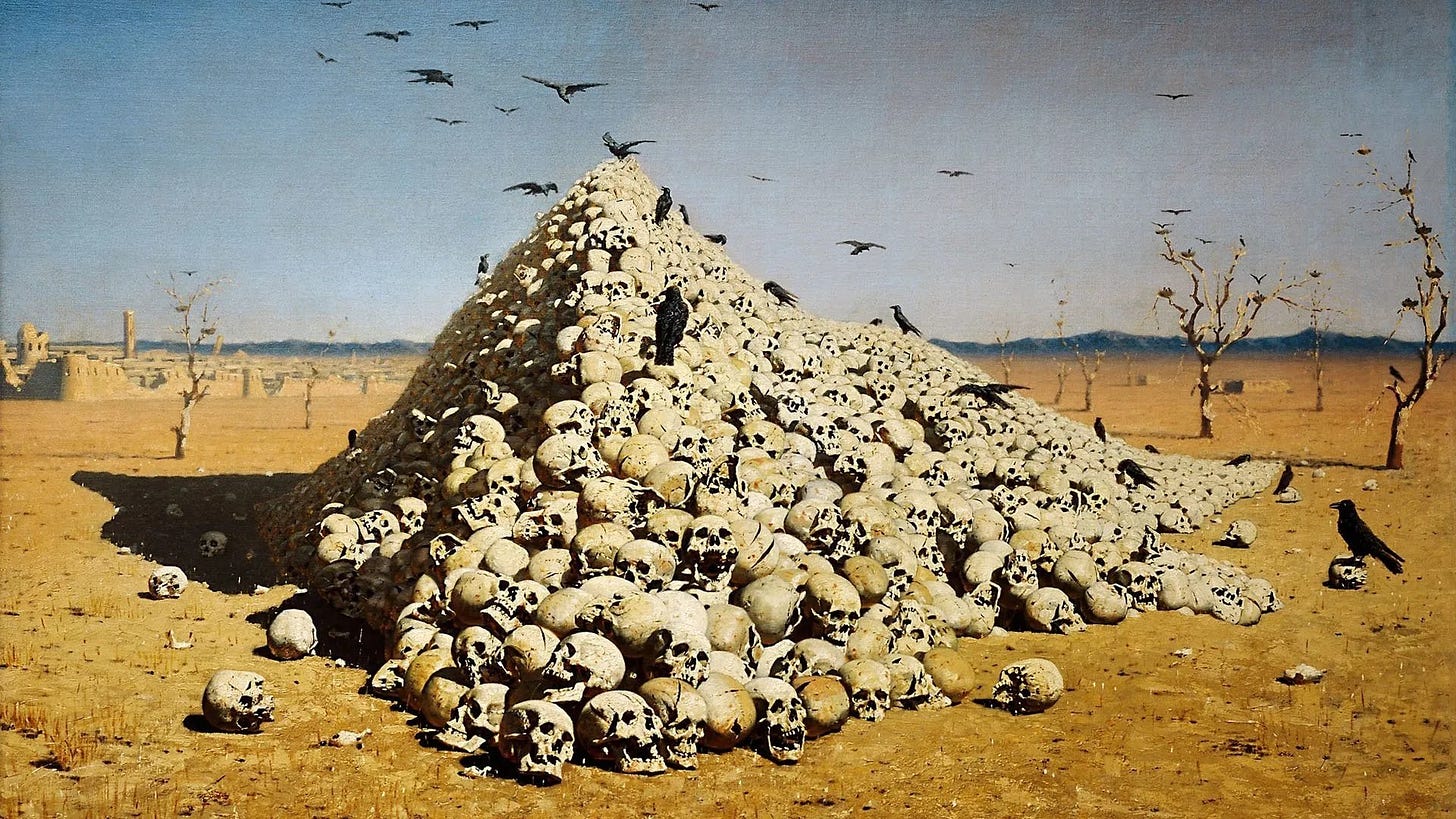

Subversion here isn’t chaos for its own sake. It’s erosion—slow, precise, corrosive. It doesn’t seek to conquer territory but to compromise clarity. The goal is a society caught in a strategic haze—unable to fight back because it can’t find where the pressure is coming from.

The West adopted Clausewitz as a tactician—fixated on lines of effort, centers of gravity, and decisive engagements. But they left the philosopher behind. They kept the structure and ignored the soul. The Russians, by contrast, inhaled the core: war as a contest of perceptions, of will, of psychological endurance.

Clausewitz warned that war was never science—it was a paradox, a volatile interplay of passion, chance, and reason. And above all, it lived in uncertainty: “Three-quarters of the factors... are wrapped in a fog.”

Western doctrine, with its rationalist optimism, tried to banish Clausewitz’s fog—deploying satellites, dashboards, and doctrines like floodlights. It treated friction as a glitch to be fixed. But for Russia, fog isn’t the obstacle—it’s the terrain. They don’t clear it. They become it.

In this new terrain, control isn’t about flags on maps—it’s about trust networks, bandwidth dominance, and cognitive saturation. The territory is no longer landlocked—it’s mental, digital, and social.

And that changes everything. While the West preps for border defense, this model builds for coherence defense. While we invest in strike capacity, the Russians invest in narrative shaping, legal maneuvering, and cyber infiltration. They don’t storm the gates—they study the plumbing.

The approach is subtle only in effect, not in intent. Pressure isn’t applied all at once—it’s metered, like a systems test. They probe. They retreat. They return. Not always to break—sometimes just to amplify the cracks we already had.

It’s tempting to mythologize this as genius. It isn’t. It’s simply ruthless design adapted to the world as it is—not the one we keep hoping it’ll be.

In this battlespace, tactical supremacy means little if strategic coherence is unraveling. While Western forces rehearse high-intensity warfighting, adversaries are quietly sawing through the scaffolding—the public narratives, shared assumptions, and decision-making tempo—that those forces rely on.

Even post-conflict phases aren’t what they used to be. Where the West sees reconstruction, the Russians see consolidation. Influence moves in when the guns fall silent—not to rebuild, but to reframe.

And Western strategy, still squinting at the old playbook, keeps waiting for flags to drop, shots to fire, lines to be crossed. But that war is fading into memory. What remains is a contest of legitimacy, narrative, and inertia.

The West is fighting 21st-century wars with a 20th-century mindset—and the Russians not only know this, they've turned that lag into a weapon.

In that war, firepower doesn’t win. Storylines do.

And until doctrine adapts to that reality, the West will keep designing weapons for a battlefield that’s already been replaced—by one that plays out in comment sections, private channels, and the quiet real estate of the human mind.

This is an excellent essay. The quote from Joseph Conrad is perfect. Clausewitz was right. Tenacity and endurance are the decisive qualities in a contest of wills. Clarity is the decisive mental quality. The West has become hedonistic and neurotic. It means they no longer see things clearly and it is relatively easy to confuse them. They always want to find the easy way out of a problem. Sometimes you simply have to accept the horrible truth.

On the battlefield they behave quite old-fashioned with meat waves, with the mass of artillery, Russia kills it's men as in the Second World War. The demography of Russia is such that Russia has always produced refugees.

This obfuscating, pompous behaviour is part of Russian culture, can be seen in the revolution of the workers, the overestimated army, Putin's fake democracy, elections with fake candidates, bending the constitution, the use of doppelgangers, war is called a special military operation.

Yes, they have improved in the modern use of propaganda, they infiltrate western governments. With an economy the size of Italy they want to be a world power, so education, health, infrastructure are at a lower level than in the West.

In terms of economic size, Canada and Italy are bigger than the Russian economy, with Spain and South Korea just behind. Having nuclear weapons is no guarantee of military success.