“We can’t rely on anything. Except ourselves. Ludicrous responsibility devolves on us, overwhelms us. In every regard, right up the present, people always have relied on each other—or God.”

George Bataille

There are thinkers who comment on the surface of events, and there are those who disassemble the deep machinery that sustains them. Giorgio Agamben belongs decisively to the latter. His work does not merely analyze crises — it reveals how crisis has become the permanent operating mode of modern power. In the early decades of the 21st century, still haunted by the unprocessed violence of the 20th — wars, camps, genocides, legal exceptions masquerading as norms — Agamben stands out as one of Europe’s most lucid and unsettling philosophical voices.

At a moment when liberal democracy celebrated itself as the final form of political life, when the post-Cold War world basked in the feverish glow of historical triumph, Agamben exposed the architecture of control still lurking beneath that euphoria. He showed that the emergency measures of the past — internment, surveillance, suspension of rights — had not disappeared; they had simply been normalized, made technical, and repackaged in the language of governance and public health.

I like Agamben mainly because reading him feels like watching someone draw with charcoal — not delicately, but violently, with pressure, with insistence. His thought doesn’t sketch; it strikes. There’s something almost physical in the way his concepts land, like hard, dark lines dragged across the page of Western philosophy. He doesn’t shade — he wounds the paper. Like an expressionist who rejects softness for the sake of truth, Agamben percusses the surface of thought until it bleeds. Each sentence feels like it comes from a place that’s had enough of precision without consequence, of light without shadow. He doesn't theorize at a distance — he pushes the idea into the world until it trembles. That’s what I admire: not just his intelligence, but the force of it. You feel it in your chest.

More importantly, He is not a public intellectual in the media sense. He refuses simplification, avoids moral reassurance, and insists on asking the questions that destabilize our most cherished assumptions: What meaning does law retain when it can be set aside whenever convenient? What is freedom worth if it depends on compliance to be allowed? What becomes of democracy when its sovereign power lies in determining who no longer belongs under its shield?

For Agamben, modernity did not overcome the catastrophes of the 20th century — it integrated them. And in an era increasingly defined by hypermodern acceleration, his thought forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: the 21st century may not be a triumphant sequel, but a refined continuation of the same unresolved violence. His philosophy, in this sense, is a form of resistance — not through protest, but through precision.

Agamben’s genius lies in his ability to think across centuries and conceptual terrains — from Aristotle’s dynamis to Carl Schmitt’s state of exception, from Benedictine rules of life to biometric passports. Like Foucault before him, he maps how modern power no longer needs an ideology to function: it governs through life itself, through the meticulous regulation of bodies, health, space, time, and potential.

But where Foucault saw a shift from sovereign violence to disciplinary and biopolitical control, Agamben reveals something far more unsettling — that sovereignty never disappeared; it simply became more subtle, more administrative, more banal. It embedded itself in democratic institutions and humanitarian rhetoric. In his major work, Homo Sacer, Agamben unveils the hidden foundation of political power as exclusion — the ability to strip someone of legal and political form, to produce what he calls bare life: a life that can be killed without it counting as murder, a life outside the realm of sacrifice, history, or mourning.

This homo sacer is not a figure of the past. It is the undocumented person rendered invisible by bureaucracy. These are not exceptions to our system; they are revelations of its inner logic. In this way, Agamben forces us to confront the fact that the European project — that imagined synthesis of Enlightenment rationality, human rights, and post-war reconciliation — was always haunted by what it excluded. What Europe refuses to face, Agamben brings to light: that its identity crisis is not merely political but metaphysical. What does Europe become when it can no longer offer meaning, only management? When it no longer aspires to universality, only to control? Agamben’s thought is the mirror held up to this slow erosion.

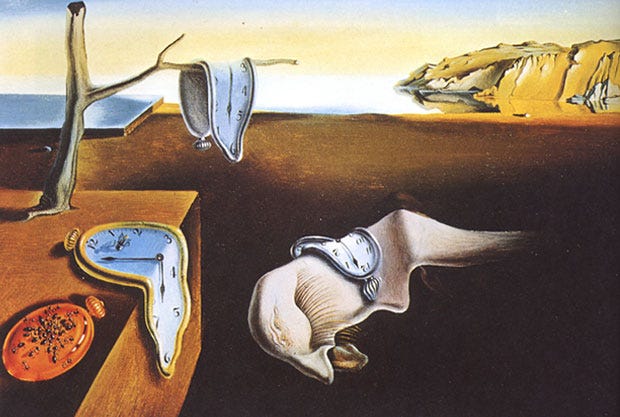

The image that captures this best is not from political theory, but from Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory. The soft, melting clocks in a barren, dreamlike landscape evoke a world where time itself has lost order, where structure no longer holds, and where everything that once seemed solid — law, history, rights — has collapsed into surreal fluidity.

This is the world Agamben describes: a hypermodernity where forms still exist, but their substance has liquefied. We still have “democracy,” “freedom,” and “law” — but they no longer anchor us. They melt in the heat of the permanent state of exception.

To understand just how far we have fallen, it is worth recalling a concept from the Renaissance — saper vedere, “knowing how to see,” a phrase Leonardo da Vinci used not only in relation to painting, but to knowledge itself. For Leonardo, vision was not passive reception but active perception: the ability to see the hidden structure beneath the visible, the anatomy beneath the skin, the law of motion in stillness. Agamben is, in this sense, a postmodern inheritor of the Renaissance gaze. His thought teaches us how to see what modern life deliberately conceals: the quiet violence of normality, the sacred residues in secular governance, the life that survives beneath legal categories. Just as Leonardo dissected corpses to understand how life moves through form, Agamben dissects political concepts to understand how power moves through life.

This is also where he diverges, crucially, from Hannah Arendt. Arendt brilliantly diagnosed the collapse of political responsibility under totalitarian regimes, and the banality of evil that made it possible. But she retained faith in political categories — citizenship, action, the public realm. She believed that the right to have rights could be restored through reinvigorated institutions. Agamben, by contrast, shows how even democratic categories themselves can become instruments of abandonment. He exposes how the law includes by excluding, how democracy governs through exception, and how freedom can become the very name of control. He sees that in modernity, the machinery of domination no longer wears a uniform — it wears a surgical mask, or a bureaucrat’s badge, or the bland language of policy.

Agamben’s refusal to adopt any clear political label — left or right, anarchist or conservative — is not indecision. It’s a philosophical position. He does not trust the logic of political categories because he sees them as part of the apparatus they claim to oppose. His goal is not to take power, but to render power inoperative. In The Use of Bodies, he develops an ethics of immanence: a form of life that cannot be separated from how it is lived, a life not subject to roles, identities, or predefined functions. Not a new ideology, but a kind of ontological sabotage.

His writing, like his politics, resists simplification. He is not a theorist of slogans or “solutions.” His work requires patience — and offers, in return, a view from a higher altitude. In The Kingdom and the Glory, he uncovers how modern governance inherits its structures from Christian theology: divine economy becomes state management, and the invisible hand becomes the angel of history. He shows us that the sacred did not disappear — it was secularized, instrumentalized, and woven into the most banal routines of modern life.

There is a monastic intensity in Agamben’s work, a sense that philosophy matters only when it risks everything. During the COVID-19 pandemic, his warnings about the medicalization of life and the normalization of emergency powers provoked harsh backlash. But he was not being reckless — he was being consistent. His question was the same as always: What kind of life are we defending, if defending it requires us to suspend the very conditions of living freely?

Stendhal once wrote, “The truth is beautiful, without doubt; but so are lies.” Agamben is a philosopher of uncomfortable truths. He strips away the beautiful lies that uphold the modern order: that law is always just, that democracy is always moral, that life is always protected. What remains is a stark but necessary clarity — and a challenge: to imagine a form of life that cannot be captured, categorized, or sacrificed in the name of protection.

This, finally, is why Agamben must be read. Not because he is fashionable — he is not. Not because he offers hope — he refuses illusions. But because he forces us to see again, and to see otherwise.

In a West that has lost its metaphysical compass, drifting between bureaucracy and barbarism, Agamben does not offer a way back. He offers, instead, the tools to perceive what might still be possible — in the ruins of sovereignty, in the silence beyond politics, in the life that remains after every category has collapsed.